How I Write a Talk

This might not work for you. But it works for me!

Giving a good talk is mostly a matter of writing a good talk and crafting a coherent presentation of that material (with or without slides or other helpers). In this post, I’m going to briefly walk through how I prepare talks. This process may not work for you at all; sometimes I read other people’s talk preparation strategies and laugh because they’re so wildly different from mine. But this way there’s one more strategy documented out there.

The strategy is the one I’ve developed over the past few years as I’ve given a couple conference talks and a bunch more weekly tech talks at Olo.

While my own approach here has a couple details that are technical, the vast majority of it is applicable to any kind of talk. In fact, a lot of this is essentially identical to certain phases of my preparation for preaching a sermon or teaching a theology class at church.

1. Brainstorm on paper.

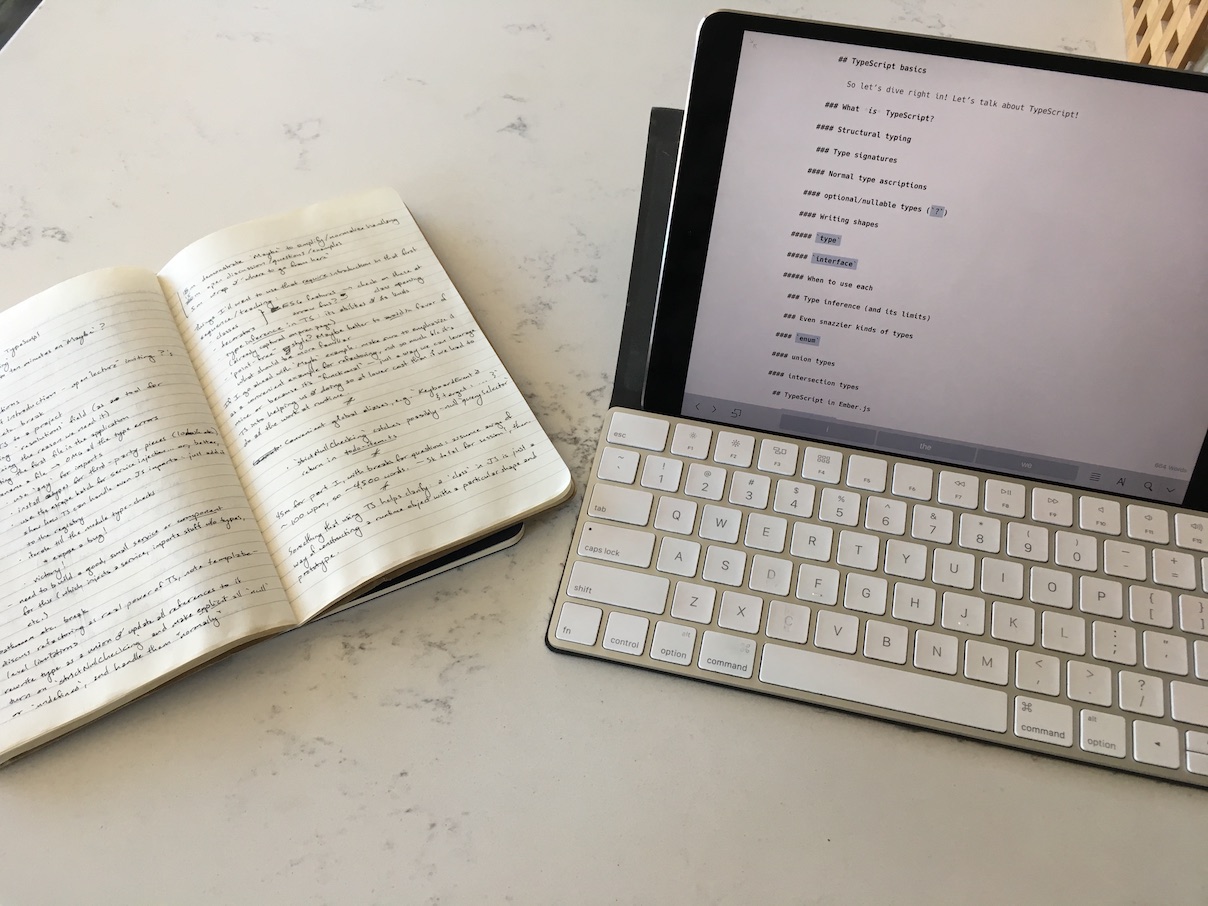

I start by writing out a bunch of different approaches I might want to use for the talk with pen and paper. Usually I grab the Moleskine I dedicate to writing ideas1 and my favorite pen and put away everything electronic. Here I’m not worried about structure or organization at all. I just jot down the things I want to cover, what the motivating idea and main takeaway is, and any secondary points I want the audience of the talk to come away with.

Sometimes this is broadly obvious because I already know how to come at the talk. Sometimes it takes multiple passes to get right. And when I skip this step, things go wrong regardless. I almost gave a really terrible version of an important internal tech talk at Olo a month ago because I hadn’t take the time to do this, and ultimately had to push back when I delivered it by a bunch as a result!

2. Write a high-level outline and map out the overall timing.

Once I have a good idea the way I want to tackle the subject, I write an outline—again, in my Moleskin with a pen. Once I map out the overall sections of the talk, one or two or very rarely three layers deep, I go through and write out how long I think each section should be. This is often the first point I have to start cutting material, because I can look at a list of eight sub-bullet points allocated to a 10-minute block and realize: no, I’m probably not actually going to get through that.

3. Draft the talk, writing it out long-form.

This is the longest part of the process, but it works wonders for me.

I start by copying the outline from my paper notebook into a Markdown-friendly writing environment.2 I turn each bullet point in the original outline into a heading. Then I expand the outline dramatically, from those high-level sections to slide-level sections: one sub-heading per slide. At this point I also add “breaks” between all the headings, which is how the web-based slides tool I use.

Next up I script the talk in detail. I know some people just throw down bullet points here; that’s not how I work. I write out a word-by-word script for what to say. Each of those headings/slides gets anything from a sentence to a few paragraphs. As I’m doing this, I keep an eye on the word count: courtesy of having done a fair number of talks this way, and having done a lot of podcasting this way, I have a pretty good feel for what a given number of words will come out to in terms of talk time.

This is also the phase where I extract bullet points, notes about images to insert, code samples, etc. Sometimes I’ll pause to write out an example in detail while working on the script; other times I’ll just leave myself a note that looks like TODO: add Doctor Who "Oh yes!" GIF here. For reference: this GIF. The script goes behind a simple textual marker (customizable in the tool I use; usually just Note:) so that it doesn’t show up on the slide and instead is displayed as speaker notes.

The important thing for me is that writing out the talk this way lets me know what materials actually go on what slides, and it also cements the content into my mind. Once it’s written, I don’t actually try to memorize it, and I don’t read from it while delivering the talk. The act of creating it this way makes the flow of the slides flow coherently. I end up with a map to what I actually intend to say in the form of the slides themselves—so they guide me and the audience together through the content in a coherent way.

Once I have this full script written out, I’ll go back over it as a revision pass.

4. Do a dry-run and edit the talk.

I now do at least one dry run for every conference-type talk—by myself in front of the computer if necessary, but preferably in front of at least a small audience. A dry run has two big upsides:

I figure out whether I’m going to hit your time or not. I take this really seriously, because I think it’s incredibly rude to both the audience and (if you’re not going last) the next speaker to go over. So if I need to trim, I figure that out by doing a dry run (and probably not any other way). Even with all my practice prepping spoken materials, I still have to tweak and trim for length quite regularly.

I get to have a feedback cycle with the actual process of presenting the material—from yourself if nothing else, but possibly also from the audience if I have one.

I’ve only gotten to do a dry run with an audience twice (for my Rust Belt Rust talk and for the EmberConf workshop I just gave), but it has been incredibly helpful both times. Having people give you feedback on what you’ve just presented can be slightly intimidating, but it’s way better to learn that the flow was off in an important way before you give a talk than during or after the presentation.

I write down the feedback I get in a dry run, or I take notes if I’m doing it by myself, and then I use those to update the script and slides I prepared in step 3 to resolve any issues I ran into. That often means cutting material; in the case of my EmberConf workshop it also meant completely restructuring part of the talk—moving the order of material around a lot. That was a lot of work, but it was also incredibly important and valuable.

To see this in practice, you can see the whole final content of my EmberConf 2018 workshop here—you can see it’s just plain text and some special markup for certain slide transitions.

5. Repeat Step 4 until I’m happy with it or I’m out of time.

Let’s be honest: it’s usually the latter, and in many ways that’s actually a good thing. A talk can be polished ad infinitum and it’s not actually helpful to polish forever. At some point the return on investment is so small relative to the time cost (which is high!) that you should just stop and give the talk.

or occasionally a white, narrow-ruled legal pad↩

Right now that’s usually Ulysses, but there are things that bother me about every such writing app I’ve ever tried—and yes, before you suggest it, that does include Emacs and Vim, along with VS Code and other programming text editors, as well as the usual plain-text writing environment apps like Ulysses.↩

Chris Krycho

Chris Krycho